Adapting to climate change is a story of have and have-nots

Happy Finance Friday and welcome to the third and final part of this mini-series on climate change and muni finance. The first issue covered pricing climate vulnerability in the municipal market, the second was about the net zero gap, and this week I’ll discuss the inequities of adapting to climate risk.

HOLIDAY PROMO ALERT! Want access to the full paid-subscriber posts? Sign up for a 30-day free trial!

Climate haves and have-nots

The previous two issues in this series talk about some of the key issues regarding climate change adaptation from a municipal market perspective. But there’s a wide range in what cities are doing and how they’re equipped to deal with climate risk.

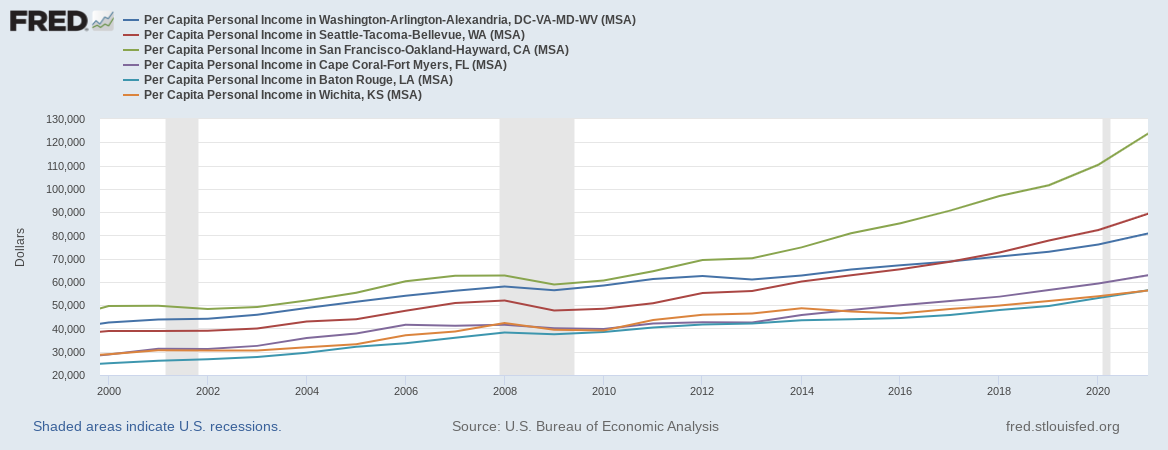

The American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy’s (ACEE) 2021 City Clean Energy Scorecard is one measure of how U.S. localities are (or aren’t) adapting to a warming climate. The report focuses on metrics like building codes, energy and water utilities, transportation policies and other measures. The top three cities ranked by the report are San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington, D.C. The bottom three are Baton Rouge, Louisiana; Wichita, Kansas; and Cape Coral, Florida.

These metropolitan areas also split the same way along economic lines:

Four of these cities also split along racial lines: Seattle is majority-white while the majority of San Francisco’s population is either white or of Asian descent. Meanwhile Baton Rouge and Wichita are majority-black. (D.C.’s population used to be majority-Black and is now 45% white and 45% Black; Cape Coral’s population is mostly white.)

Another consideration is a recent Brookings Institution study that looked at how cities were adapting to flood risks. It found that adaptation is higher in cities with higher flood risks, and that adaptation increases after major hurricanes.

So, what does all of this tell us? The regions with the money and the economy to back it up are more likely to successfully adapt to whatever a changing climate brings. Tellingly, the Brookings study was done by analyzing the financial disclosures of 356 cities and it also found that adaptation is significantly higher for cities that have more unrestricted funds relative to expenses. Conversely, “most cities without an adaptation plan cited budgetary capacity issues as a barrier for climate change preparation,” the authors wrote.

Inequities contribute to climate migration

The World Bank predicts climate change could create as many as 143 million "climate migrants" by 2050. But by no means does this lead to millions of dried out Californians leaving en masse for places like Michigan or Wisconsin where there’s more water and lower taxes. In fact, a recent study from the University of Chicago found that climate-change-induced migration in the next 50 years is expected to increase population in the West.

The Dust Bowl in the 1930s is one modern example that provides insights into what factors into a migration driven by environmental conditions.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Long Story Short to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.