EV owner whiplash

More places are increasing fees on EV owners while also incentivizing purchases.

Welcome back, readers! First, thank you to those who have responded to my question about how you use Long Story Short. This information really helps my decision-making. If you haven’t responded, it’s only one question so please do!

On to the meat which today is my follow up on the cost of EV ownership (read Part I here) and government incentives. Or (unintended) DIS-incentives, as is increasingly becoming the case. Read on.

Targeting EV owners to pay their fair share

Many state and local governments have created emissions reduction targets and a big part of that is turning their fleets over to electric vehicles. But they can’t do it alone—consumer take-up is what will really move this needle and up until recently, the pace has been glacial.

Some of this uptick on the graph is because EV prices have decreased. But the real game changer the past two years has been the federal government’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the Inflation Reduction Act—both which offer grants and incentives related to electric vehicles.

EV buyers can get a federal tax credit for their purchase, a sales tax credit from their state and a rebate or tax credit for installing a home charger. These incentives knock thousands of dollars off the total upfront cost and is helping to spur adoption.

But here’s the rub: Gas taxes are a primary funding stream for state transportation trust funds. This model used to work well because it was a “user pays” system where the more you used the roads, the more trips you made to the pump and gas taxes you paid. EVs don’t contribute to that even though they’re using the roads too so, governments are toying with other ways of getting ongoing revenue from EVs. Options include:

I wouldn’t blame EV owners for getting whiplash. On the one hand, they can potentially get a federal tax credit worth $1,000 to install a home charging system and on the other hand, they’ll shell out much more than that over time in additional registration fees.

As I noted in Part I of this newsletter, the cost-benefit-analysis on EVs (excluding any personal feelings on carbon footprint) varies depending on where you live and your driving habits. But a lot of those metrics get drastically altered with any of the above scenarios.

Let’s look at what happens in Maryland, where prices run close to average and where lawmakers are dabbling in some of these policy responses.

Bypassing the gas tax

Earlier this year, Maryland launched a pilot program testing the mileage-based user fee (MBUF). Instead of paying the 46-cents-per-gallon tax on gas at the pump, participants pay a per-mile fee. EV owners can participate too but for them, an MBUF is a tacked-on cost without a potential offset (as is the case for hybrid and traditional car owners who are benefiting from lower prices at the pump).

Even hybrid owners might see higher costs, depending on their road usage. In Part I of this newsletter, I noted that it would around a decade for a hybrid or EV owner living in Maryland and driving 15,000 miles per year to make up the higher upfront cost and start saving money.

But under an MBUF, the Maryland hybrid owner would pay about $132 more each year in fuel costs while the EV owner pays $233 more. That cuts significantly into my savings-over-time calculator—potentially negating any chance of realizing operating cost savings compared with a gas-powered car.

Years to realize upfront cost savings: EV, hybrid

Maryland is also following a well-worn path and increasing car registration fees for EVs—expected to be an additional $125 bill each year. Here’s what happens in July 2025 after those fees go into effect.

Years to recoup higher EV, hybrid costs with fee increase

Worth asking:

How much will these additional costs for EV owners hamper adoption?

Will that affect Maryland’s net-zero emissions by 2045 goal?

➡️Crosswalk Labs emissions data tool: look up your city.

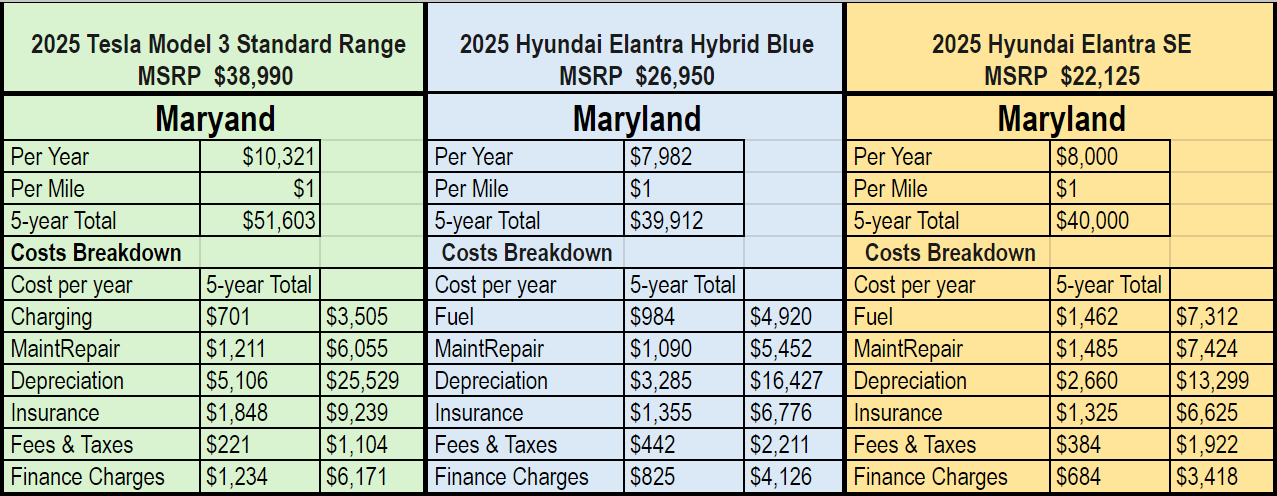

Keep in mind: These estimates are likely best-case-scenarios. I did not include the cost of insurance (which tends to be higher) or maintenance (which tends to be lower), because that data wasn’t predictable enough for me. But by AAA’s calculation, which does include those costs plus depreciation, financing and fees, EVs cost way more over the first five years.

Notable: Oregon offers a registration discount to EV owners participating in its MBUF, OReGO. “In many instances,” writes the OreGO service provider Azuga, “this winds up being less than the increased registration fees.”

Perception vs. reality?

I’ve noticed more EVs and charging stations in my neck of the woods and figured if EVs are catching on in farm county, then we’ll all be buying them soon! But that’s just not the case. (Yet.)

EVs stand out while all the other regular cars blend into the background. So, we remember that Tesla in the parking lot but there’s a mental blank spot for the five other cars parked around it.

Some EV advocates have noted that lawmakers may be operating the same way in thinking that EVs are bleeding state transportation funds dry. Despite how much we notice them electric vehicle uptake is not the culprit problem right now, noted Baruch Feigenbaum, head of transportation policy at the libertarian Reason Foundation.

“While electric vehicles and hybrids are a growing part of the problem, and we talk about them a lot and we need to solve them,” he said, “the biggest problem is your traditional internal combustion engine—your Toyota Camry that gets five more gallons per mile than it did 20 years ago.”

Additional sources

Trends in electric cars – Global EV Outlook 2024 – Analysis - IEA

Maryland Mileage Based User Fee_FAQ-1.pdf (tetcoalitionmbuf.org)

Maryland testing a program that would charge drivers based on mileage (wmar2news.com)

Great analysis. I do think that if "consumer take-up is what will really move this needle," in your words, the needle will stay in a low zone for a darn long time.

Personal transportation is the hardest nut for this technology to crack -- all sorts of other vehicle classes are better suited to an EV switchover, from city buses to urban delivery runabouts to taxi fleets -- and while the financial disincentives you outline constitute a big hurdle, so too do all the usual complaints about value for money, range, thinly installed chargers, charging time, and battery life / safety / disposal.

Fleet operators of all varieties can fix those issues far faster and more economically than they'll be mitigated for the motoring public at large, so why not concentrate migration incentives there? (NB. I'll never be able to own a plug-in because I live in a high-rise and park in a communal garage that is not wired for chargers and never will be owing to installation costs. I sometimes think EV boosters believe the whole world lives in suburban homes with two-car garages.)

I think this is a 50-year project, all told, and individually owned vehicles will start to help "move the needle" en masse in two or three ownership cycles, e.g. 25 years from now.