Explaining funky pension math

And why we really don't know for sure what governments will owe their retirees.

Happy Finance Friday readers! Stanford University just published a policy paper about pensions and I spoke with one of the authors (and LSS subscriber) Oliver Giesecke earlier this week. He and co-author Seamus H. Duffy are state and local finance scholars at the university’s Hoover Institution, which focuses its public pensions research on their cost to governments and advocates for a more conservative approach to valuing public retirement systems.

The paper that was released Thursday makes a number of valuable points about pension accounting that I hadn’t considered. I’ve been writing about public pensions so long I almost forgot how weird this particular corner of public finance can be. This week, I’ll break down the funky math used for pension liabilities and how this new research fits in.

Some pension fun facts

Until the 1970s, governments didn’t set aside money for their retirees’ guaranteed income (pensions). Instead, that money was budgeted annually.

A “fully funded” pension means that the chunk of money set aside today is projected to accumulate enough over time to cover all the projected pension benefits for current employees in the plan and retirees. (Guess what the key word is here…)

Most public pensions were fully funded in the early 2000s.

In nine states, the majority of public employees do not receive Social Security income.

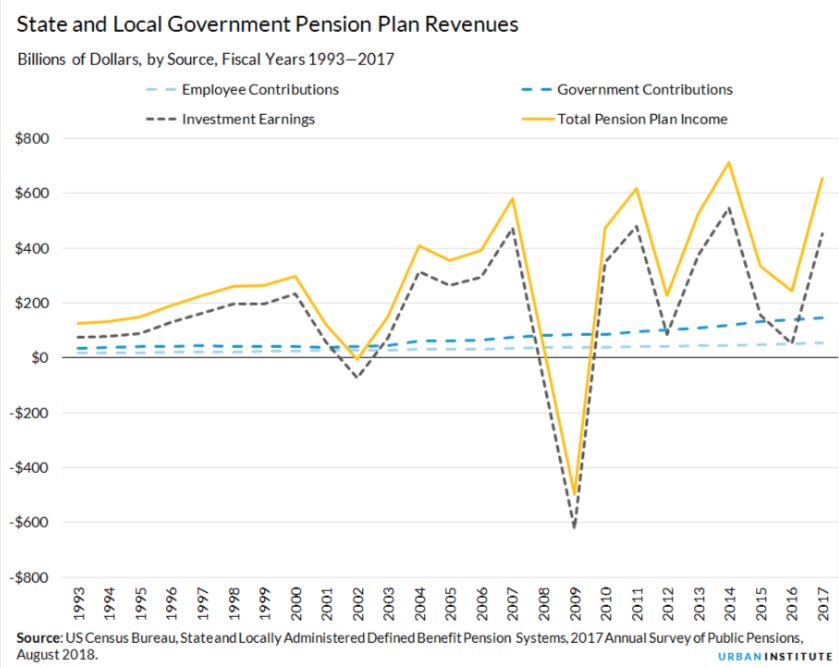

Pension systems earn money over time mostly through investment earnings, which have become more volatile in this century (see chart below). A small percentage comes from an automatic deduction from worker paychecks and the rest from annual or semi-annual deposits from the government.

Read more

The Urban Institute’s state and local pension explainer

Public Plans Database’s national pension data

Mary Pat Campbell on pension funding (and not funding)

When you assume…

The only certain number in pensions is the base income that current retirees are getting. Everything else is basically an educated guess. In the accounting world, these are called assumptions.

The amount of money that needs to be saved and invested each year to cover one public employee’s retirement ultimately depends on what they make in their top earning years, when they retire, how long they will live, whether they will receive Social Security, how much the employee is contributing (which changes with pay raises), and—most importantly—how much money those investments earn over time.

Pension plan funding (what the government contributes) depends a LOT on these assumptions. Those of us with a 401(k) or IRA also make educated guesses when planning our own retirement, but public pension actuaries have to make these assumptions for an entire population of workers. And they do that with two big twists.

No matter how much money is in the pot (pension system)…

A public employee’s retirement salary is set upon retirement. With a 401(k), worker retirement income is dictated by what’s in their individual pot.

Public employees can retire with this guaranteed income after they reach a certain age (as early as 45 years old for law enforcement and usually between 55 and 65 for other workers.)

Investment returns are crucial to this balancing act. Most pension systems now assume an average annual return of 7% over the long run. As you can see in the two charts below, that may have been a safe assumption 20 years ago. But if you consider more recent trends, that may not necessarily be true.

The actual math is more complicated but in essence, assuming a 7% average annual rate of return means:

A fully funded pension system with $100 million in assets today assumes those assets will grow to roughly $196 million over a decade.

If that pension is underfunded by $30 million, that unfunded liability doubles if the government doesn’t start putting more money in than it originally planned.

BUT, if these plans only return an average of 6%, everything gets worse.

Now consider other assumptions around how much is actually needed for each employee’s retirement such as life expectancy. A retiree on a $50,000 pension that outlives expectations by 10 years is at least $500,000 more than actuaries planned for.

In other words, ‘fully funded’ means, “We think we have enough set aside as long as everything goes how we expect it to.”

Bottom line, even today’s well-funded plans might not actually have enough set aside to cover what they’ll ultimately need. But no matter what transpires, governments (and their taxpayers) have to make up the difference.

When the math changes

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Long Story Short to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.