What Omicron means for state and local finance

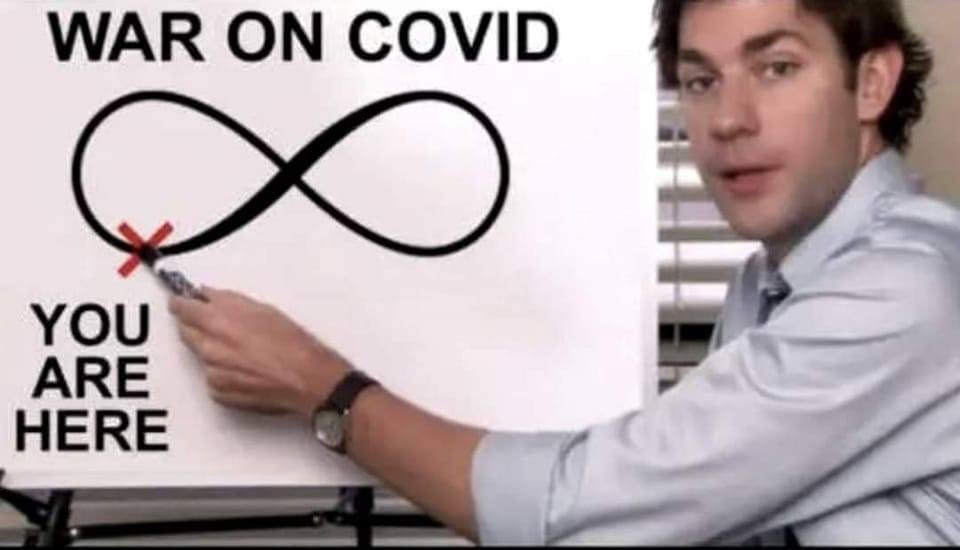

The holiday season these days is a time for fun, cheer…and a rise in Covid-19 cases. Piling on to that, the emergence of the Omicron coronavirus variant is a new cause for concern. This week, I’ll take a look at how this new variant could affect state and local finances.

The economic impact of Omicron

It is too soon to say for sure how the effects of the Omicron variant, which was reported in California on Wednesday, could affect the economy. But Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell warned Congress on Tuesday that the new variant could have a negative impact.

“The recent rise in Covid-19 cases and the emergence of the Omicron variant pose downside risks to employment and economic activity and increased uncertainty for inflation,” Powell said. “Greater concerns about the virus could reduce people's willingness to work in person, which would slow progress in the labor market and intensify supply-chain disruptions.”

Fitch Ratings said Monday that policy responses such as severe lockdowns could have an “inflationary effect” if they constrain labor supply recoveries or exacerbate global supply-chain shortages and bottlenecks.

Concerns: In the event of severe lockdowns, Fitch said “the most exposed sectors, such as tourism and international travel, will be disrupted, and the shift back to services from goods consumption may also slow.” Public health systems, many of which are run by counties, could also be overburdened if hospitalization rates increase.

The good news: We are learning how to adapt. Plus, vaccinations have so far helped reduce hospitalization rates. Where we work and what we buy might change during these waves, but the economic engine doesn’t turn off like it did in March 2020. Look at what happened in the U.S. during the third quarter, when the Delta variant was surging: Real GDP slowed compared with the previous quarter, but still grew by a decent 2.1%.

Which places are vulnerable?

Metro areas with slower job recovery rates and places where vaccination rates lag are more likely to be affected by a new surge in the coronavirus.

The following chart from Fitch shows regional unemployment rates and rates adjusted to include those who have left the labor market but aren’t filing for unemployment.

Boston and New York are driving much of the Northeast’s numbers. Both cities saw a nominal uptick in their overall unemployment rate and declines in leisure and hospitality jobs. Baltimore has also experienced job declines in leisure/hospitality, as has Philadelphia. In the South, Orlando has recovered only 55% of its pre-pandemic jobs through September, according to Fitch, while New Orleans has recovered just 26%. New Orleans’ recovery has also been hampered by Hurricane Ida.

In the West, Las Vegas’ recovery has stagnated after posting big gains earlier this year. Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area have also slowed and regained only about half their lost jobs, according to Fitch. And in the Midwest, Chicago, Cleveland and Milwaukee have recovered fewer than 58% of their pre-pandemic jobs.

When it comes to vaccinations, localities in the deep south as well as North Dakota, Tennessee, West Virginia and Wyoming are potentially vulnerable because statewide vaccination rates are below 50%. This increases the chances that hospital systems in these places could be strained by a new virus surge.

What it means for local budgets

With more federal aid now at hand, cities and counties should have the financial cushion they need to get through a surge. But there’s more to it than that. How localities use their federal aid hints at longer-term fiscal trends.

As I wrote about last week, state budgets are in pretty good shape. However, local government budget health varies widely. A recent ICMA survey found that more than half of local governments want to use American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) dollars to replace lost revenue—a one-time expense.

Let’s look at New Orleans, which has the unfortunate distinction of having a stagnated recovery and is in a state with low vaccination rates. A year ago, the city was staring at a deficit of up to $140 million—nearly 14% of its operating budget. The city ultimately cut $100 million from its budget and now Mayor LaToya Cantrell wants to use $77 million in ARPA funds to restore some of those cuts. In other words, at least 20% of the city’s fiscal relief funding could go toward returning to the status quo.

Compare that with another southern city: Austin saw a boost in revenue last year and the city’s current budget increases spending on things like parks and mental health. The city is also directing 40% ($100 million) of its ARPA funding to add to the $200 million it had already invested in a program to help Austin’s 3,200 homeless people.

Why this matters: The pandemic’s uneven impact on state and local finance means that some places are still organizing their Monopoly money and picking their game piece while others are halfway around the board and buying up all the good properties. Three-quarters of mayors say that ARPA funding will enable them to accomplish “transformative” goals. But any new surge in the virus could potentially widen that gap between localities that are already in growth mode and those that are still trying to get back to their pre-pandemic budgets.

A comment from the New Orleans chief administrative officer says it all. “We’re not doing shiny new programs,” Gilbert Montaño told the New Orleans Advocate. “We’re trying to maintain structure with some of the programs we have.”

Related: The recovery from the Great Recession also produced a widening gap between certain credits.

What I’m watching

Inflation. Fed Chair Jerome Powell also told Congress that the Federal Reserve now believes inflation will continue to rise into the next calendar year. That could increase the cost of issuing short-term debt for some local governments.

Halstead Bead v. Lewis. This lawsuit by an Arizona-based jewelry supplier was recently filed in the Eastern District Court of Louisiana and backed by three conservative-leaning groups. It’s an online sales tax fairness case that its backers are hoping will go to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Notes from the field

I recently spoke with Chuck Maniace, a vice president at Sovos, about sales tax trends. We both noted there are now fewer state auditors due to retirements and wondered what that would mean for tax auditing efforts. Chuck speculated that departments would rely more on analytics. Of course, he’s motivated to say that because Sovos is a tax software firm. But he does have a point. Here’s what he said:

“Is the future of auditing digital? We talk to a lot of auditors and some are still squarely grounded in that traditional, physical review of records and an office visit. But I do see a possibility where states...allow for more data-driven (compared with human-driven) audits. Legislatures would have to spell out the digital audit requirements but I imagine a process similar to others where sellers have a digital file they give to departments of revenue and that's used to conduct an audit.”

That’s it for this week and if you’ve made it this far, I’d love your feedback. Was this too long? Too short? Was the meme at the top in poor taste or did it make you laugh? Please don’t hesitate to reply to this message with your thoughts.

And don’t forget that subscribers to the free newsletter will see the full version for just a few more weeks. The paywall goes up in January so if you like what you see, please consider converting your subscription! Get more details from my announcement post.