The cost of becoming a 'waste magnet'

Chester, Pennsylvania officials welcomed a new trash incinerator in the 1990s. Now it’s one of the most toxic in the country.

Happy Finance Friday, readers! It’s time for another update on Chester, Pennsylvania’s bankruptcy case which is still pending approval in federal court. The city receiver’s team recently gave a presentation on their goals for creating a healthy revenue structure going forward. A top concern was the city’s heavy reliance on industries that negatively affect the local population.

The evolution of Chester’s waterfront from a hub of industry and middle-class jobs to a trash-strewn stretch of land with poor air quality and a high concentration of poverty is a stark one. But it’s not unique. Dozens of majority-minority communities have endured a similar degradation over the last century.

How Chester got to this point and what the city receiver’s team wants to do about it is illustrative of the challenges other communities face as they try to undo decades of harm caused by racist economic development practices and environmental injustice.

“What Chester makes makes Chester”

For nearly 50 years, this slogan blazed atop the Philadelphia Electric Co. substation at the south end of Chester’s waterfront. Created by the electric company in the 1920s to promote the city and inspire residents, the sign was Chester’s equivalent to Los Angeles’ “Hollywood” sign.

When it was erected, Chester was home to major industries like Sun Ship and Ford Motor Co., and a host of smaller support factories that produced things like custom modeled glass and uniforms. In 1973, it was dismantled because power stopped flowing to its lights after an operational change at the substation. That also happened to be a decade when the city lost one-sixth of its population and went from majority-white to majority-Black.

Today, the industries that Chester’s budget relies upon most are trash, gambling and incarceration. Maybe it’s a good thing that the sign isn’t up anymore because those industries are far from inspiring.

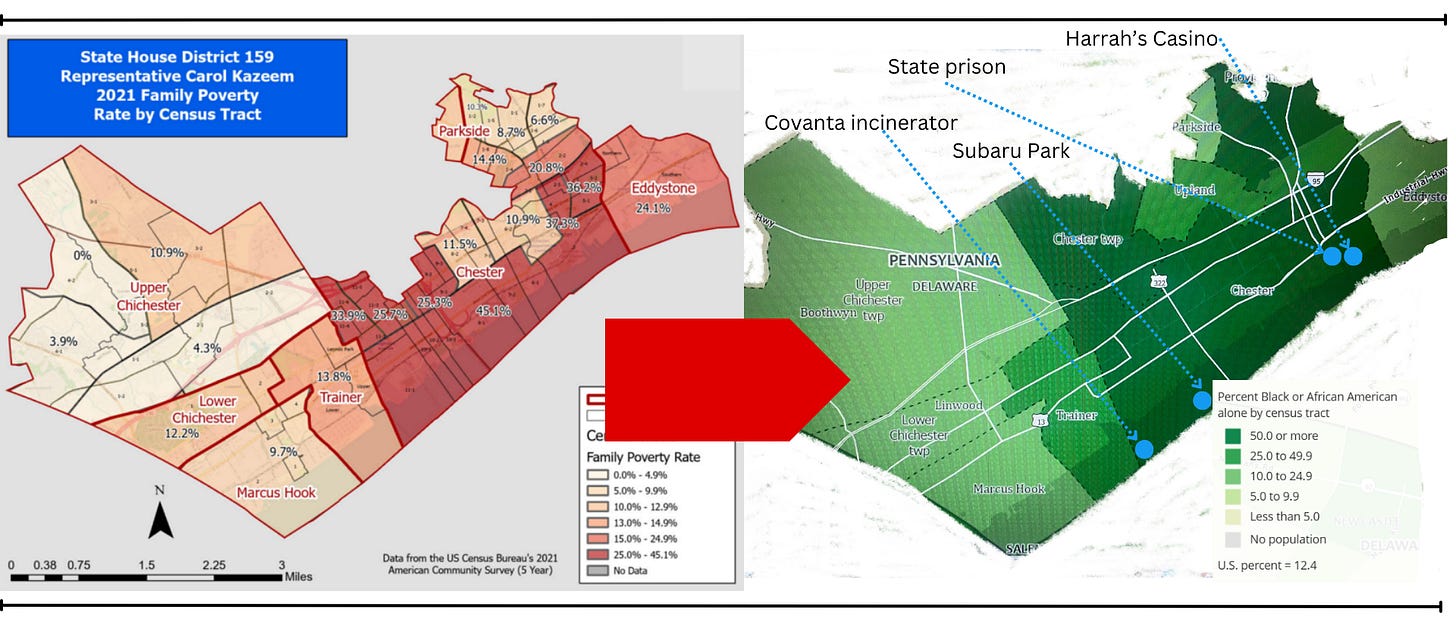

Receiver Michael Doweary and his team want to use the city’s recovery plan as an opportunity to change this dependance. Chester is not only dependent upon these industries, the incinerator is doing more environmental harm to the city’s residents than good. And with a family poverty rate of more than 45% in the neighborhood along the waterfront, those harms fall disproportionately on those who can least afford it.

“If there is a serious desire to see different economic development uses…the first step is to try to eliminate or reduce financial dependence on revenue from industries that negatively impact the public,” Vijay Kapoor, Doweary’s chief of staff, said at the recent Municipal Financial Recovery Advisory Committee.

Doweary’s team acknowledged that weaning the city off this reliance was going to be difficult and slow. With an annual operating budget of about $40 million, more than one-quarter comes from trash and gambling. The incinerator (a.k.a. the Delaware Valley Resource Recovery Facility) contributes $5 million and Harrah’s Casino provides $10 million.

“Chester residents, to be clear, also share some of the benefits of those entities,” Kapoor said. “But it's Chester residents, particularly those who live along [the waterfront], who experience all of all of the negative consequences.”

‘Waste magnet’ economic development

The desire to build an incinerator in Chester originally came from city officials in the late 1980s as a way to revitalize the city's economy. The story is covered in detail in the book, “Race and the Politics of Deception” by Christopher Mele, which Kapoor referenced.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Long Story Short to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.