How to steal a water utility

The bankrupt city of Chester says governing control of its regional water authority was taken from it without compensation—or public debate.

Welcome back, readers! It’s been almost two years since the Philadelphia-area city of Chester, Pennsylvania, filed for bankruptcy and I figured it was a good time to revisit one of the biggest sticking points in the case: water.

As usual with Chester, the backstory is unique and takes some explaining. This newsletter will focus on the city while my next installment later in the week will look at the pros and cons of selling off troubled city assets for cash.

Was the Chester Water Authority stolen from the city?

That is the claim being made by City Receiver Michael Doweary’s team in recent public meetings and in an October legal filing in the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Among other things, the filing argues that Chester was twice-wronged over the past century and namechecks certain members of the region’s Republican party machine.

The first offense was in 1939, when the city’s population was growing and it was about to become an epicenter of production during WWII. Chester issued $5.9 million in bonds (more than $133 million in today’s dollars) and used about $1 million of those bond proceeds ($24 million in today’s dollars) to buy the privately-run Chester Water Service Company.

But, the filing says, the price was marked up at the last minute by Chester political boss, John J. McClure.

“As subsequently revealed, the City did not buy the Chester Water Service Company directly from Federal Water Services Company,” states the filing, citing several historical sources. “Rather, Chester purchased [it] from a strawman acting for a cabal led by McClure. The McClure conspirators” swooped in to buy the company first for $750,000, “then immediately sold it to the city for $1,000,000… Thus, the CWA began its existence with corrupt political operatives swindling $250,000 (equal to over $5.6 million in 2024) from the citizens of Chester.”

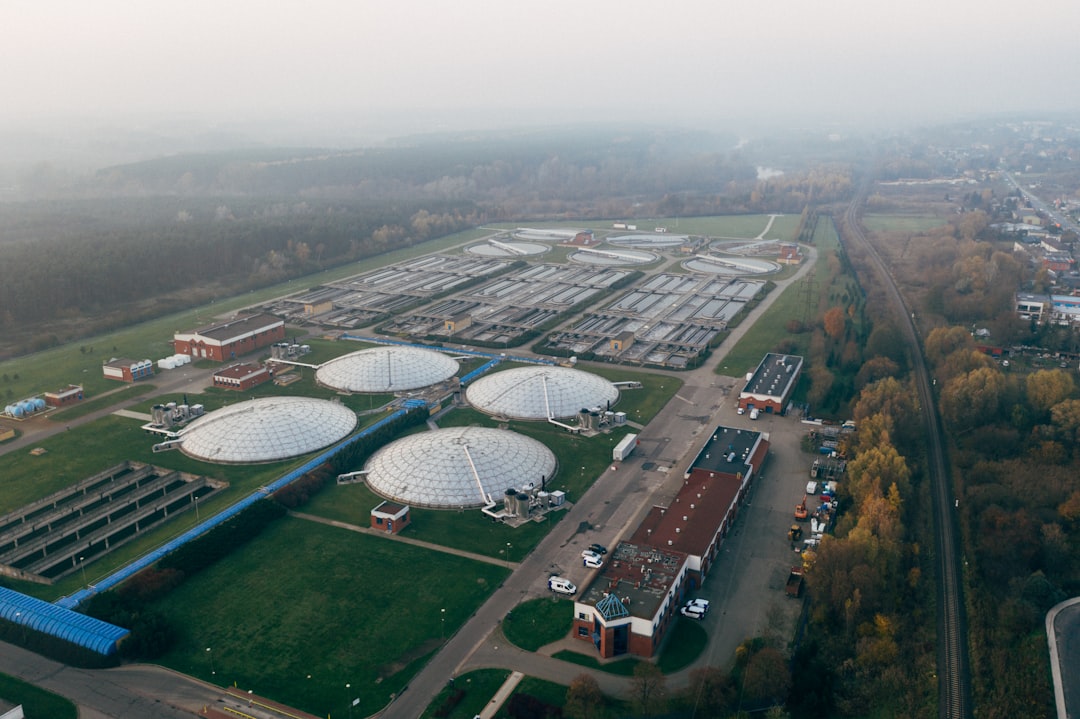

For the next 73 years, only the city had the authority to appoint members of the governing board though the CWA served customers outside the city boundaries. Over time, the CWA continued to expand and became one of the region’s largest public water systems, serving more than 200,000 people across 37 municipalities in Delaware and Chester counties.

But in 2012, Chester lost that control with no monetary compensation, thanks to a state legislative amendment added to a budget bill the night before that bill passed. Though Chester was not named in the amendment, which targeted board governance of regional water systems, the language was conveniently specific enough so that it only applied to the CWA.

Get the details

Read the receiver’s October court filing

Chester receiver presentation: How CWA Board Control was Taken from Chester

During a presentation last month, Doweary’s chief of staff Vijay Kapoor noted that “a law this significant would be open to hearings and public debate” and would be discussed in media stories. “None of that happened,” he said. “There were no hearings, there was no comment from elected officials, there were no stories ahead of time. Residents never even knew this was happening.”

The result of Senate Bill 375, which dealt with ratepayer representation, was that the water authority’s five-member board expanded to nine members and split appointees between the city and two surrounding counties.

“Moreover, conveniently,” the filing adds, “the new members of the CWA were entirely Republicans…including the Republican incumbent who lost the Chester mayoral election in 2011.”

The result was that Chester, which had incorporated the authority and overseen its expansion, lost its sole right to govern it. But it took another decade for the fight over governance to come to a head.

Blocking a quick-fix sale

In 2016, the state legislature passed “fair market value” (FMV) legislation, which consumer protection attorneys have called “a potent lure for cities that need money for their ailing budgets.” FMV laws have been passed in 14 states and allow a city to sell its water system for an appraised value closer to what it would cost to replace the system, rather than the commonly used and much lower “book value,” which reflects the age and original purchase price of the assets.

That led to the private water utility Aqua America’s unsolicited offer to buy the CWA in 2017 and a years-long legal battle between the CWA board and the city over who had the right to sell it. In 2022, the Pennsylvania Commonwealth Court ruled that Chester is the sole owner of the water authority, prompting the city council to approve Aqua’s $410 million offer.

The CWA appealed the sale to the state Supreme Court. Citing the dissenting opinion in the Commonwealth Court ruling, CWA argued that its growth since incorporation in 1939 “was financed by ‘water rates paid by the Authority’s ratepayers, not by City funding.’” Noting that “this is 2021, and [the 2012 governance change] has been the law for nearly ten years,” the CWA said the lower court “erred in concluding that…the City has the exclusive authority to repossess and sell the CWA’s assets, without the consent of Delaware and Chester Counties.” (Emphasis included.)

When the city filed for bankruptcy, the water case was put on hold and the two sides went into mediation. The receiver’s bankruptcy recovery plan includes retaining the CWA as an asset and his team’s filing this month urges the court to move the case forward and resolve the appeal:

The City formed the CWA for the benefit of its residents. From its inception, however, the CWA has been used to take advantage of those residents, including as recently as 2012, when the City was surreptitiously stripped of control over the board of the CWA against the City’s will and without compensation. Similarly, various quick-fix projects have been proclaimed the solution to the City’s decades of financial distress, only to be followed by continued financial distress. The Receiver seeks to turn the tide of history; to exercise the same rights as every other Pennsylvania municipality that has incorporated an authority, to put the assets of the CWA to work for the benefit of the residents of the City, and to implement a long-term solution to the City’s financial distress.

In the next installment, I’ll look at the easy money provided by selling city assets—and whether it pays off.