The pros and (mostly) cons of privatizing water

Running a municipal water utility is expensive for localities. But selling it off can be even more costly.

Welcome back, readers! This newsletter is the second part of a two-parter on Chester, Pennsylvania’s, water fight. In this one, we’ll look at the pros and cons of selling off troubled city assets for cash.

Part I Recap

Chester’s Plan of Adjustment in U.S. Bankruptcy Court includes generating annual revenue by “monetizing” its water assets, “while keeping them in public hands.”

But there’s a big ol’ fight over who actually owns the Chester Water Authority (CWA) and, therefore, who gets to sell it (or not).

A private company has offered to buy the CWA for $410 million.

Easy money—too easy

Chester’s pensioners want the CWA sale to go through because selling it would solve—on paper anyway—Chester’s overwhelming retiree liabilities that account for the bulk of its debt. Other troubled Pennsylvania cities like Scranton and York have taken that route in over the last decade, opting to sell off their water/sewer utilities to wipe away debt and avoid expensive infrastructure improvements.

Pennsylvania American Water’s deal to buy York’s water system was for $235 million on top of an estimated $17.5 million needed for upgrades.

But, as I’ve written about before, there’s a lot more going on in Chester than just debt problems. Selling the water system to a private company may very well be the answer to fixing the city’s unfunded pension liability. But it won’t come close to addressing the short-sighted governance and mismanagement that bankrupted the city in the first place.

That’s true of any distressed city looking for an easy out to its debt.

Why privatize water?

Pennsylvania is one of about a dozen states that have passed “Fair Market Value” (FMV) legislation, which makes offloading a public water utility more enticing. Instead of a negotiated sale price based on the government’s books—which account for depreciation but not the value of future revenue flows—FMV increases the sale price by requiring a market valuation.

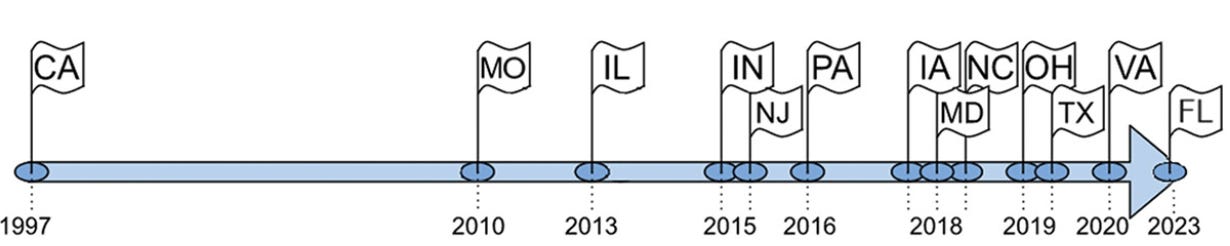

Timeline of passage of fair market value legislation in US states

(McKiernan, Warner analysis in the International Journal of Water Resources Development)

On the surface, letting someone else handle all those investments while getting a big fat check to spend on services, stabilize the budget, etc. is better for taxpayers. But the new owner will still want to recoup their purchase and investment costs through rate hikes, and raising the price of the sale means more money to recover.

A private company can spread the costs associated with upgrading an aging system in one place across its national or statewide customer base and thus reduce the per-customer rate hike for that investment. But—it also means that all customers will pay the cost of acquiring more water systems.

Recent research has found:

Among the largest water systems, private ownership is related to higher water prices and less affordability for low-income families.

In states with regulations favorable to private providers, water utilities charge even higher prices.

This affects more than one in ten Americans who pay their water bills to a private company. But the figure is much higher—30% to 59%—”in nine states, including several with industry-friendly policies,” notes this 2017 investigative feature by the Indiana-based nonprofit journalism organization, Inquire First.

The story notes that 2014-2016 lead contamination crisis in fiscally distressed Flint, Michigan, has helped spur privatization. Old pipes and outdated treatment plants are expensive to replace, and complying with EPA consent decrees can be costly.

“The pitch is, ‘Listen, if you don’t want Flint to happen to you, then you know you should probably privatize,’” Richard Verdi, a Wall Street analyst, told Inquire First.

Appealing—at first

Like Chester, Scranton had spent decades in Pennsylvania’s fiscally distressed municipality program. But it finally exited in 2022.

One of the administration’s crowning achievements in stabilizing the city’s finances was selling its water utility. As I wrote in 2016 for Governing:

Selling the system gave Scranton cash to help pay off some of its pension and high-interest debt. It also unloaded an EPA-required $140 million upgrade to the system to protect the Chesapeake Bay onto [buyer] Pennsylvania American Water. The requirements would have meant a 5 percent rate hike each year for 25 years. Instead, the sale stipulated the private company could raise rates no more than 1.9 percent on average for the first 10 years.

Even with that stipulation, the Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission in July 2024 approved rate hikes of 10.7% for water and 6.4% for wastewater. The water company said the increases for Scranton customers will help pay for $1 billion in planned water and wastewater system investments through 2025.

A recent story by veteran Scranton Times-Tribune reporter Jim Lockwood notes that the commission has also launched a nine-month investigation into “water-quality and service concerns and complaints raised by customers and local legislators in the water company’s northeastern service territory.” Still, the commission denied Scranton’s request to reconsider the rate hikes.

Related

What's Behind the Push Toward Privatizing Water Systems? (Governing, 2024)

Sewer rates soar as private companies buy up local water systems and Pennsylvania is ‘ground zero’ (Stateline, 2023)

Who ultimately pays

Chester’s receivership team has said they want to keep their system in public hands but is still soliciting offers for a lease/operator agreement or sale. If they are granted that right, officials will have a difficult road ahead navigating potentially competing interests including residents, retirees, ratepayers, and creditors—all while getting its budget structurally balanced for the long-term.

Managing water systems anywhere these days is full of tough choices. Thanks to chronic underinvestment in water system maintenance and upgrades, the way we capture, store, clean and distribute water has become more costly this century. Consumer bills are rising and will probably continue to do so as water authorities and governments look for revenue to pay for overdue infrastructure improvements.

So, owning a water utility is downright expensive and, in some cases, unaffordable. But NOT owning a water utility is also costly in different ways, particularly in terms of public accountability.

Either way, consumers will pay the price.

Liz, Thank you for the coverage. I am a security analyst who follows American Water Works Company (AWK). I believe that you are correct that selling out leads to increases in water bills for community residents, but clearly in most cases, as I believe that you point out, the selling communities have found it difficult to comply with EPA regulations on water quality. Upgrades cost money and municipalities often face the ire of their constituents when rate increases are proposed. It seems that people are more willing to accept rate increases that come from private companies. I think that you should also note that the acquirors still have to get proposed capital budgets and rate increases approved by state public utility commissions, so there is oversight. Some municipalities have also found the middle ground by contracting out the management of the local water companies to private operators, rather than selling outright.